Who Were We in 1940?

March 11, 2015

By Stephanie Ortenzi

A look back at what life was like 75 years ago, when Bakers Journal was founded

Library and Archives Canada, PA108300 (Main); Life Insurance Companies of Canada/Canadian Medical Association, 1943 (right)

Library and Archives Canada, PA108300 (Main); Life Insurance Companies of Canada/Canadian Medical Association, 1943 (right) Major milestones have a way of making us look back. Bakers Journal turns 75 this year, and we’re taking a look at what the baking business was like in the magazine’s early days.

A new book is rich with information about who Canadians were culturally and economically in those days. Historian Ian Mosby is the author of Food Will Win the War. He examines food and nutrition in the daily lives of wartime Canadians and the government’s role in what and how we ate, and how we conducted business.

At the start of 1940, we were three months into war with Germany. Commercially, we could handle volume production through conveyor-belt systems thanks to industrial advances made during the previous war. But we weren’t in the best health. Agencies surveyed the country’s nutritional behaviour between 1930 and 1941. “The most alarming discovery,” writes Mosby, “was that the vast majority of families were failing to consume sufficient quantities of nutrients.” One set of findings showed that only three per cent of families were eating enough calories. Only seven per cent ate enough protein. Diets were dangerously low in vitamins and minerals. Most malnourished of all were mothers and children.

Food Rules, Rationing and Economic Restraints

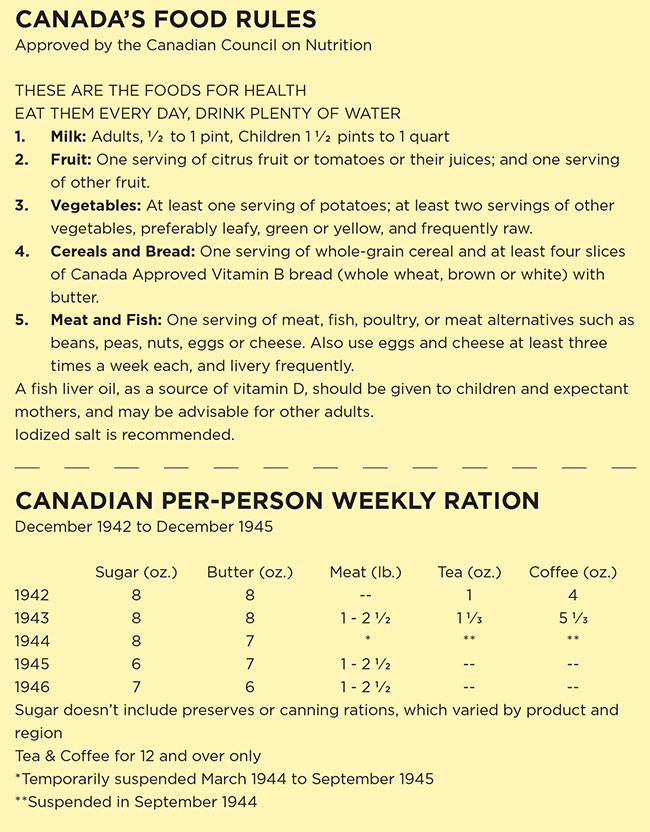

Three public policies defined the war for Canadians. Canada’s Official Food Rules became the nutritional standard. Rationing restricted scarce and valuable commodities like sugar, coffee, tea, butter and meat, for both home and commercial life. And the Wartime Prices and Trade Board (WPTB) would take historical control of how we became a wartime nation.

The Food Rules were announced very early in the war and called for basic requirements in the essential categories—like milk, meat, fruits and vegetables. But in the bread category, we’re introduced to “Canada Approved Bread, with Vitamin B.” The government required it be made with nationally sourced vitamin B, which meant milling the flour more coarsely and leaving behind more bran and germ.

Adults were asked to eat four slices of this bread every day with butter, a challenge and a source of annoyance. Rationing allowed only eight ounces of butter per week, which gave new meaning to the notion of a source of food spread too thin.

The Food Rules weren’t perfect, nor were they enough to solve our malnutrition. Public health was monitored throughout the war. A 1943 survey found over 25 per cent of Canadians were not getting enough milk or cheese, 40 per cent were not getting enough bread and cereals, and 83 per cent were not getting enough fruit. Luckily, we were doing well in vegetables, meat and eggs, but we still had a long way to go.

While the food laws seemed generous, rationing was not. The food trade was vulnerable to quotas on scant ingredients like sugar and cocoa. Bakeries could not sell iced cakes, hotdog buns and sliced bread, because they were thought to be wasteful and inefficient. Foodservice was expected to observe “Meatless Tuesdays,” and toward the end of the war, Fridays went meatless as well.

Still, rationing had a little wiggle room. For example, you could eat “off-ration” if you ate in a restaurant, hotel, bakery or wherever prepared foods were sold. But you’d also be subject to quota limitations in foodservice, which was allowed to give customers only one-third of an ounce of butter and no more than one cup of coffee or tea each.

There was even more wiggle room for physical labourers. During harvest, farm workers could have two extra meals a day. Industrial workers could have off-ration tea and coffee on their breaks. Loggers could have four times the allowed meat and three times the sugar.

Watching for Inflation Tipping Point

Federally, the WPTB was established two days after the Allies declared war in Germany, seven days before Canada was officially at war. Almost immediately, the board took control of buying, selling and distributing commodities and consumer goods. It paid subsidies to primary producers, set production quotas, guarantees, price controls, and wage and rent controls. The economy was considered to be in a perilous state.

“This unprecedented state intervention into the consumer economy,” writes Mosby, “was spurred by an inflationary spike between August 1939 and October 1941,” when Canada was very nearly fully employed. Wages were up, and so was food spending. We spent 18 per cent more on milk products, 12 per cent more on meat, 24 per cent more on eggs, and 20 per cent more on tomatoes and citrus fruits. Inflation was climbing. Food prices were up 24 per cent, but we couldn’t produce food fast enough. There was a tangible fear that this inflation would go the way of the inflationary spiral at the end of the first World War, which led to the Great Depression.

Agriculturally, the board also made a large imprint. Between 1940 and 1943, it cut prairie wheat acreage by 42 per cent, increased feed grain production by 72 per cent, flax seed production by 800 per cent and pork production by 250 per cent. We had what looked like the makings of a real war machine, except that shortages and food lines persisted throughout the war.

Dozens and Dozens of Doughnuts

Another book helps us see what our industry was like in 1940. Steve Penfold’s 2008 work, The Donut: A Canadian History, looks at a food’s cultural iconography, but it also tells a few interesting stories about an idea that got very big.

There once was a wartime Ontario baker who was in debt to the mill for 440 bags of flour. No matter how fast or how well he worked, profit eluded him. He had one employee, a Brit, who had an idea. He wanted to make doughnuts. They were cheap to produce and had potential for scaling up. The Brit’s idea was not original or unique, and that family operation didn’t get profitable until after the war, but doughnut shops were popping up across the country throughout the war.

Commercial baking was already automated. “By the First World War,” writes Penfold, “some large Canadian bakers were adopting early continuous flow methods [of production], applying electricity to run mechanized kneading bins, conveyer belts to move bread at precise intervals, automatic cutting and wrapping.” According to Penfold’s book, in 1940, Canada was making eight million dozen doughnuts, and as many as 20 million dozen in 1945.

The war was good for the doughnut. In 1942, an American doughnut company produced the “Nutro” doughnut, which won the approval of Canada’s director of nutritional services, who said the Nutro had “twice as much Vitamin A, B and Riboflavin as one slice of ordinary white bread,” writes Penfold. Added the director: “It also appears that under the standardized method of manufacture, only a small amount of fat is absorbed in frying.”

That would never fly today. Luckily, today, we don’t look for nutritional reasons for permission to eat a doughnut. We’re under no illusion about what it is. We’re OK with that.

Print this page

Leave a Reply