Wheat goes for a wild ride

April 29, 2009

By Stephanie Ortenzi

A sack of flour on its shelf in the bakeshop has tiny phantom numbers spinning around it – like electrons around an atom, or like a cartoon character’s chirping stars after being bonked on the head.

|

|

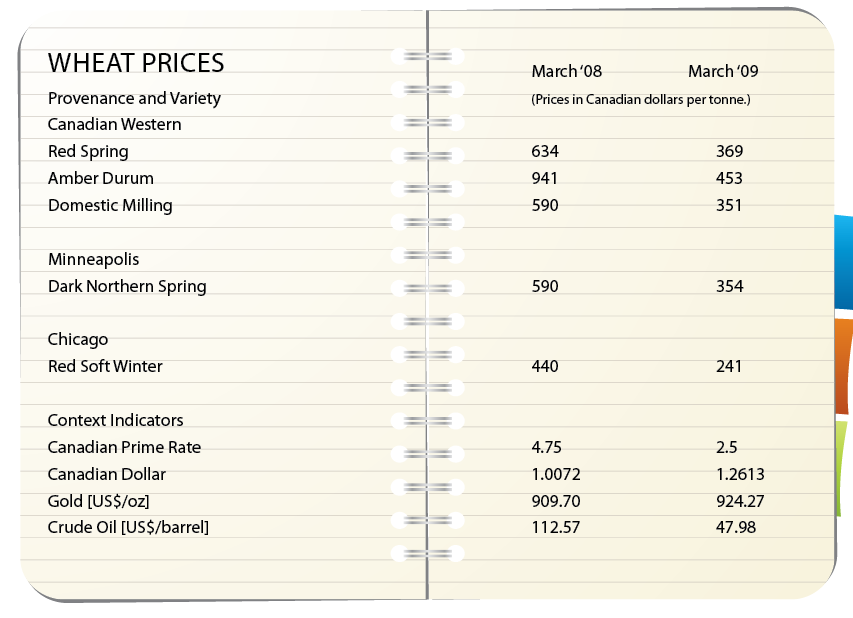

| The economic crisis continues to keep the price of grain uncertain, but the weaker Canadian dollar and lower ocean freight rates have been mitigating factors.

|

A sack of flour on its shelf in the bakeshop has tiny phantom numbers spinning around it – like electrons around an atom, or like a cartoon character’s chirping stars after being bonked on the head.

Wheat has been getting bonked on the head for a couple of years, and it has rollercoaster commodity pricing to show for it.

Looking back, it turns out the price of wheat had been on the rise long before its big climax in mid-2008. As the price climbed, the market drew gamblers.

It wasn’t about food anymore, but big, fast profits. Regulatory bodies lightened up on their regulating. Investors grew powerful through their sweet-spot loopholes. Food commodity investors began dealing in abstractions, and index and pension funds got richer. Farmers reaped few benefits, because profits were ravaged by the higher costs of getting the wheat to market.

The short version of the story begins in January 2008.

|

|

| Sources: www.agr.gc.ca/mad-dam , RBC Current Economic Indicators April 3, 2009

|

The year isn’t two days old before the predictions are out: wheat prices are going to rise. A few days later, forecasted crop shortages crank up the price from $160/metric tonne to $430. By mid-February, the price is at $500, and a week later it’s hit $798. By early March, market watchers are hoping the price will settle at $600, which it did – for a while.

In July, Statscan reports the price of flour is up 44 per cent from the year before.

Talk turns to increasing acreage. More wheat, more opportunity to reap profits from these high prices at market – except that gasoline is up 28 per cent from the year before.

By August, industry watchers were predicting record crops, and that prices would hold. Statscan reports that the month’s four per cent rise in food prices was pushed by a 13 per cent jump in baked goods. Inflation overall is at its highest level in more than five years.

In October, Ron Bonnett of the Canadian Federation of Agriculture draws attention to the rising costs of growing wheat – fuel, fertilizer and the availability of credit. He tells the Canadian Press that these factors make it “extremely difficult to plan and pencil out a reasonable profit.”

A C.D. Howe Institute study released in November says that the Canadian Wheat Board has delivered poor results for agriculture, which sparks a debate on the best way for the board to do right by its farmers.

By the end of the year, the anticipated increased planting never materializes. Globally, planting is down three per cent. Revenues are at record highs, and the cost of taking wheat to market has retreated only temporarily.

By early January 2009, markets are still reeling. Crude oil is at $100/barrel, and wheat futures have bottomed out at $168/tonne. Durum gets sold aggressively abroad to reduce the Canadian surplus.

On Feb. 26, the Canadian Wheat Board reports that the world economic crisis continues to keep the price of grain uncertain. Some good news, says the board, is the weaker Canadian dollar and lower ocean freight rates, but “major customers continue to buy on a hand-to-mouth basis, as their attention increasingly turns to new-crop prospects.” That can’t be good.

Guess, Hedge, Bet, Win, Lose, Draw

Enter the speculators. The markets are established on the principle of risk. Where there’s money to be made, players have studied the angles. Where there are angles, there are loopholes.

In a May 20, 2008, article titled “Who is responsible for the global food crisis?” Globe and Mail reporters Sinclair Stewart and Paul Waldie break down what happened last year on the commodity markets; how the agricultural product became so far removed from the forces establishing its value; how deregulation spoiled speculators’ natural benefit to the commodity markets; and how loopholes from Reaganomic policies opened the door to the abstract and artificial valuation of energy companies such as Enron.

The price of wheat takes its cue from commodity markets, influenced on many fronts. Asian markets present a tremendous demand for food. Crops are often failing because of poor weather, most recently drought. The growing production of ethanol puts a strain on wheat, because wheat has to make up the slack for feed, which is worth less at market.

North American pension and index funds are major players in commodity markets. They began investing heavily and increasingly in agricultural commodities as a way to diversify. In 2003, their investments were valued at US$13 billion. Five years later, their bottom line was US$260 billion.

Because agricultural markets are small, relative to stock markets, the Globe report explained, “The amount of cash pouring in, gives these funds substantial clout.” Their sheer heft can sway the value of a commodity toward a profitable position for the fund.

These funds became powerful because of a loophole left by deregulation policy championed by Reaganomic Republican Wendy Gramm, chair of the U.S.

Commodities Futures Trade Commission. The policy was drafted to help an offshore energy company, which turned out to be Enron’s predecessor, leaving the door open for non-agriculture interests to invest freely in food futures.

When the Republicans lost control of Congress, Gramm joined the board of Enron, and an era of corporate over-valuation began.

In Canada, the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan was one of the earliest funds to invest in food futures. In 1997, the investment was $100 million. Today, it sits at $3 billion, making it one of the world’s largest commodities investors.

Between 2000 and 2007, the price of wheat increased 147 per cent.

Playing with our food

In April 2008, the high cost of food had created a global crisis. Some market watchers believed prices were being forced up unnaturally, that the loophole was making the investment in food an abstraction rather than putting a price on human sustenance.

A distinction was drawn between “commercial” players, such as farmers, grain elevators and processors – all those directly involved in the food chain – and the “speculators,” investors such as index funds, hedge funds and pension plans, who have no visceral connection to the commodity itself.

There is a quick assumption that speculators in general ratchet up market prices for a personal profit, but the Globe report points out that speculation performs a vital role in the markets. If farmers want to hedge against their risk by selling a futures contract to deliver wheat a year from now at $8 a bushel, they need speculators willing to buy the contract in a bet that prices will rise by the delivery date.

Regulation is the key. It first appeared in 1922 as the Grain Futures Act and later the Commodities Exchange Act of 1936, each time limiting how much money “non-commercial” players can invest.

Nearly a year after the worst of wheat commodity prices, regulating how the markets invest in food futures is still unfinished business.

Fortunately, somewhere something is always looking up. The prime-lending rate is 2.5 per cent, down from 4.75 per cent last year. Crude oil is selling for $48 a barrel, down from $112 last year. Canadian Western Amber Durum Wheat is selling for $453/tonne, down from $941. While some count their profits, others count their blessings.

Stephanie Ortenzi is a food-service marketing writer with 15 years of experience as a fine-dining chef. She can be reached at steph@ortenzi.ca or 416-624-9758. Visit her website at www.pistachiowriting.com .

Print this page

Leave a Reply