Mixing up Change, Part 1

December 3, 2007

By Cliff Leir

West coast baker Cliff Leir writes about efforts to revive a heritage wheat variety – and along with it a culture of food.

A few weeks ago on CBC Radio, I heard a group of farmers from Saskatchewan chatting about growing low protein wheat for biofuel production as an economically viable alternative to growing and selling wheat for food due to current commodity prices. I support alternative fuel sources but this illustrates the continuing problem of food not being valued and the economic squeeze on independent farms. This issue has been widely discussed amongst groups concerned with food security. There are many initiatives being put forward in many areas of the food industry, including bread production, to try and address this and create more sustainable food systems. I’d like to recount the ongoing story of one project started in Canada in hopes that it may be an example to learn from, so that hopefully further mistakes may be avoided and more people may become involved.

A few weeks ago on CBC Radio, I heard a group of farmers from Saskatchewan chatting about growing low protein wheat for biofuel production as an economically viable alternative to growing and selling wheat for food due to current commodity prices. I support alternative fuel sources but this illustrates the continuing problem of food not being valued and the economic squeeze on independent farms. This issue has been widely discussed amongst groups concerned with food security. There are many initiatives being put forward in many areas of the food industry, including bread production, to try and address this and create more sustainable food systems. I’d like to recount the ongoing story of one project started in Canada in hopes that it may be an example to learn from, so that hopefully further mistakes may be avoided and more people may become involved.

In the spring of 2003, a woman named Mara Jernigan contacted me at my bakery (Wild Fire Bread and Pastry in Victoria, B.C.). She was head of the Canadian Slow Food movement’s Ark of Taste Project, which aims to rediscover, catalog, describe and publicize forgotten flavours. Mara asked if I would try baking with an old variety of wheat that the group was trying to bring back into production. From there it all fell into place. I had originally been inspired to try milling grain myself after meeting Dave Miller. He’s a veteran baker who, after spending years baking in larger operations, finally set up a baking studio out of his house in rural California. He dealt directly with a wheat farmer, milled the grain himself, baked it in a wood fired oven and sold his bread at local markets, and seemed to make a decent living doing it. I don’t recall if Dave mentioned any problems he had, I just remember the statement, “it’s easy. Grain goes in the top, flour comes out the bottom.” That was enough for me. We were already baking in brick ovens and that was going pretty smoothly, why not go all the way?

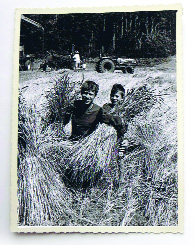

Red Fife’s Canadian roots can be traced back to 1842 in what is now Peterborough, Ontario. David Fife and a woman who was only entered into history books as “his wife” planted and grew five seeds that a friend from Scotland had sent them (the seeds had originated in the Ukraine). The first year, their cow ate two of the five heads of wheat before Mrs. Fife came to rescue. The three remaining heads of wheat had a beautiful red hue and they survived and matured ahead of everyone else’s wheat. Over the next 15 years, farmers in the Peterborough area bulked up seed and enjoyed reliable harvests of a wheat that became known as Red Fife, known for its prized flavour and baking qualities. By the 1880s, Canadian agronomists were looking for a grain that could be grown on the prairies to stabilize the struggling settlements there. Red Fife matured reliably early enough for farms to flourish and by the end of the century had been crossbred with Hard Red Calcutta to make Marquis. Canada was establishing itself as the “bread basket of the world.” Marquis matured a week earlier than Red Fife, causing the strain of wheat to fall out of favour over the next quarter century, leaving it, for the most part, to farming lore and seed banks.

Having researched its founding history in wheat cultivation in Canada, Sharon Rempel, a professional agronomist with decades of experience working with heritage wheat varieties on an organic farm, concluded that Red Fife was the genetic parent to almost all the Hard Red Spring Wheat grown in Canada. Despite this, there was no supply of this historic variety of wheat with which to bake. Over fifteen years ago, Sharon started with half a pound of Red Fife seed at the Karomeos Grist Mill and Farm and bulked up enough seed to supply a few dedicated farmers on the prairies by the new millennium. In 2003, Marc Loiselle, a fifth generation farmer of organic grains in Saskatchewan, and his wife, Anita, sent out 20 kg of Red Fife from their family farm for us to evaluate at the bakery. They believed in the integrity of their work and were interested in seeing it being used directly in a bakery instead of being blended out and shipped to who knows where.

I thought that varietal breads were surely the next step. Ultimately, local varietal wheat and local wild yeast resulting in bread of real terroir (this is a food and wine concept that, roughly translated, means embodying the taste of the land or region) would be the greatest thing since … well, sliced bread would pale in comparison. Armed with enthusiasm and ignorance, I, along with Mara and Mike Doenel, a local farmer who had been exploring possibilities of local grain production headed off to Pat Richart who operates Salt Spring Flour Mill. She had the same Austrian Stone mill as Dave Miller, except her stones were 14” and his were 42”. Still, grain in the top, flour out the bottom. And what flour! Big particles of bran highly contrasted with fine white endosperm and incredible aroma. I had only been in a few mills but I love that smell almost as much as the fresh bread out of the oven. It smelled so good I grabbed a handful of kernels and started chewing on them till they formed a pasty mass in my mouth. As my saliva began to break down the sawdust like gruel it became even sweeter and wheatier tasting. A far cry from a baguette but it had potential. Pat gave me a bag of whole meal flour and did a remarkable job sifting out the bran to create an almost-white flour very similar in appearance to the flour I had brought back from Poilane in Paris a few years earlier.

Now these are stories which add a romantic notion to our work, but the realities of running a bakery and making a living can be a very different tale. However, culture is something that is very important to me, both in the sense of my little bubbling bucket of it, as well as the revitalization of social culture. Fine loaves of bread rely equally on the quality of ingredients used and the skill of the baker. In order to maintain integrity through the whole process, it is arguably necessary to have a relationship of support and understanding between the farmer, miller and baker. If there were more of a social culture around food, and particularly around bread, that included everyone from the people in the fields to the people loading the ovens in the middle of the night to those sitting around the table, then there might be a greater appreciation and value for a simple loaf of bread resulting in a better living being made by all involved.

In my next column, I’ll continue with the saga of baking with small production, varietal wheat and the thrill as well as the challenges faced by the farmer, the baker and the customer.

Cliff Leir sold his half of Wild Fire Bread and Pastry in the spring of 2005 and is now building ovens and baking bread for his family and friends while planning his next bakery opening in summer 2007 in Victoria B.C. Last year, Marc Loiselle and his family harvested 140 metric tonnes of Red Fife. Cliff is still working with Marc and other farmers and bakers to strengthen farmer-baker relations. Contact Cliff at: midnightbreads@yahoo.ca with comments or questions.

Print this page

Leave a Reply