The Final Proof: November 2009

November 2, 2009

By Stephanie Ortenzi

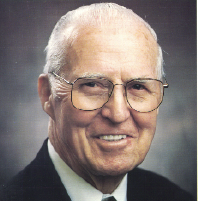

In celebration of Dr. Norman Borlaug – “the greatest human being who ever lived” – who changed how wheat is grown, and saved millions of lives.

|

|

| Dr. Norman Borlaug

|

Who thinks of funny magicians Penn & Teller as sources for a story? Blogger-politico Anthony Steele, for one. Me, for two.

I got the heads-up on Twitter from Globe and Mail writer Ivor Tossell. He tweeted that Steele’s blog was worth looking at and cited the title, “The death of the greatest human being who ever lived.”

OK, I thought to myself. I’ll bite. Who is the greatest human being who ever lived?

I was happy to click through to find a familiar face that was easily worthy of the accolades.

Agricultural scientist and humanitarian Norman Borlaug died in September at 95.

I originally came across Borlaug’s achievements three years ago, when I was writing culinary biographies for The Food Encyclopedia. The subjects were people whose food-related advancement over the past 25 years would continue into the next quarter century. He more than qualified.

Borlaug was born in Iowa in 1914 and went to the University of Minnesota, where he earned a bachelor of arts degree in forestry. He was all lined up for a forestry job, but when it fell through, he dug into graduate work, specifically plant science. Borlaug’s PhD is also from the University of Minnesota.

In 1943, the Rockefeller Foundation joined forces with the Mexican government on a project around crop failure and food shortages. Borlaug was recruited to be director of the wheat program, and it was here that he created his infamous dwarf wheat, a high-yield, disease-resistant strain.

Here’s the why: shorter plants expend less energy on growing what is essentially something inedible – the stalk and its sections – and more on growing the valuable grain. A stout, short-stalked variety easily supports its kernels, whereas tall wheat often bends over when it’s close to harvest. This makes reaping more difficult and cuts off much of the plant’s access to sunlight during the final stages of growth.

Watching Mexico’s harvest increase 300 per cent in the first year, Borlaug began looking at India and Pakistan. He arrived just as the war between India and Pakistan broke out, but neither he nor his crew, which included Mexican trainees from the earlier project, were daunted. They planted while explosions of warfare ignited visibly nearby.

When India and Pakistan’s wheat yields grew 400 per cent, Borlaug decided to dwarf rice plants, which he did at China’s Human Rice Research Institute. And on it went.

Crunching the numbers

What’s the grand total of lives he’s saved? Says Steele: “Borlaug saved between 200 million people and one billion people, depending on how you do the math.”

Borlaug himself does some quick math for the Penn & Teller video: “There are 6.6 billion people on earth and we can only feed four billion. I don’t see two billion volunteering to disappear.”

In his 1997 profile of Borlaug in the Atlantic Monthly, Gregg Easterbrook writes, “He is believed to be the primary person responsible for the fact that throughout the postwar era, except in sub-Saharan Africa, global food production expanded faster than human population, averting the mass starvations being forecast at the time.”

Borlaug won the Nobel Peace Price in 1970, and although he’s not a household name, the international academic and agricultural communities knew the value of his work. They gave him 28 honorary doctorates of agriculture, five doctorates of agricultural sciences, three doctorates of letters, one doctorate of law, one doctorate of agriculture and 16 international doctorates from countries on all continents.

Protesting GM crops

Borlaug’s work is often confused with the high-yield, genetically modified (GM) crops developed by agribusiness to speed toward a fat bottom line. Borlaug did all of his work in the countries and areas suffering – and in many cases dying – from hunger.

No good deed goes unprotested. So it is with Borlaug’s work. Easterbrook writes about the detractors who point to the environmental effect of these new crops, to which Easterbrook counters: Is it greater or lesser than the toll of human lives lost to hunger?

To clarify, GM crops are altered using molecular genetics techniques such as gene cloning and protein engineering. An example is corn that has the pesticide Bt engineered into its genetic makeup to make it resistant to certain pests. Bt is a natural pesticide and is said to never naturally find its way into corn seed. Hybrids, used in Borlaug’s work, are cross breeds of compatible types intended to create a plant with the best features of both parents.

Commentators, Easterbrook adds, said it would be wrong to increase the food supply in the developing world and that it’s better to let nature do the dirty work of restraining the human population. Despite the ugliness of the idea, Easterbrook hauls out the statistics proving the opposite to be true. High-yield agriculture halts population growth, and it moves feudal societies away from high-birth/high-death rates toward low-birth/low-death rates.

“I want to see science serve a useful purpose,” Borlaug told Penn & Teller (I can’t believe I just said that), “and improve the standard of living for all people. You can’t build a peaceful world on empty stomachs and misery.”

On the web: www.youtube.com/watch?v=tIvNopv9Pa8

Print this page

Leave a Reply